Researchers at Tufts University and Harvard University’s Wyss Institute have created tiny biological robots that they call Anthrobots from human tracheal cells that can move across a surface and have been found to encourage the growth of neurons across a region of damage in a lab dish.

The multicellular robots, ranging in size from the width of a human hair to the point of a sharpened pencil, were made to self-assemble and shown to have a remarkable healing effect on other cells. The discovery is a starting point for the researchers’ vision to use patient-derived biobots as new therapeutic tools for regeneration, healing, and treatment of disease.

In a published in Advanced Science, the researchers discovered that bots can in fact be created from adult human cells without any genetic modification and they are demonstrating some capabilities beyond what was observed with the Xenobots. The discovery starts to answer a broader question that the lab has posed—what are the rules that govern how cells assemble and work together in the body, and can the cells be taken out of their natural context and recombined into different “body plans” to carry out other functions by design?

In this case, researchers gave human cells, after decades of quiet life in the trachea, a chance to reboot and find ways of creating new structures and tasks.

By reprogramming interactions between cells, new multicellular structures can be created, analogous to the way stone and brick can be arranged into different structural elements like walls, archways or columns. The researchers found that not only could the cells create new multicellular shapes, but they could move in different ways over a surface of human neurons grown in a lab dish and encourage new growth to fill in gaps caused by scratching the layer of cells.

Exactly how the Anthrobots encourage growth of neurons is not yet clear, but the researchers confirmed that neurons grew under the area covered by a clustered assembly of Anthrobots, which they called a “superbot.”

The advantages of using human cells include the ability to construct bots from a patient’s own cells to perform therapeutic work without the risk of triggering an immune response or requiring immunosuppressants. They only last a few weeks before breaking down, and so can easily be re-absorbed into the body after their work is done.

In addition, outside of the body, Anthrobots can only survive in very specific laboratory conditions, and there is no risk of exposure or unintended spread outside the lab. Likewise, they do not reproduce, and they have no genetic edits, additions or deletions, so there is no risk of their evolving beyond existing safeguards.

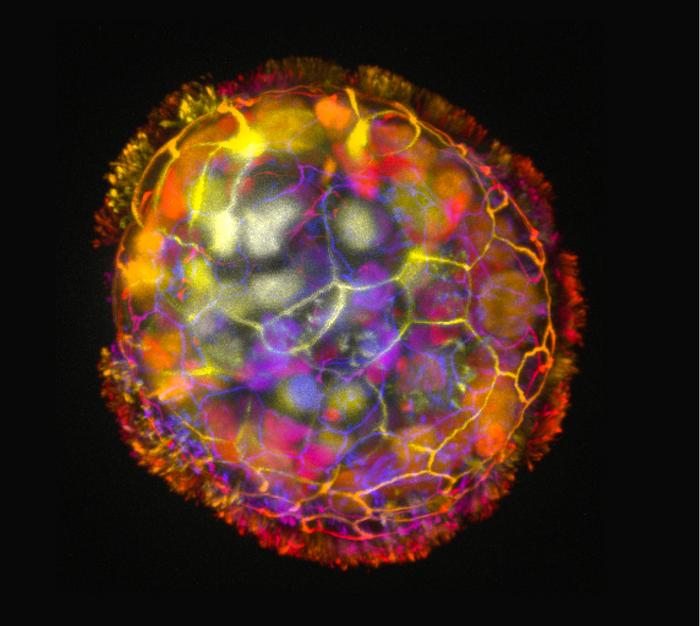

Each Anthrobot starts out as a single cell, derived from an adult donor. The cells come from the surface of the trachea and are covered with hairlike projections called cilia that wave back and forth. The cilia help the tracheal cells push out tiny particles that find their way into air passages of the lung.

The researchers developed growth conditions that encouraged the cilia to face outward on organoids. Within a few days they started moving around, driven by the cilia acting like oars. They noted different shapes and types of movement – the first. important feature observed of the biorobotics platform.

Because the researchers ultimately plan to make Anthrobots with therapeutic applications, they created a lab test to see how the bots might heal wounds. The model involved growing a two-dimensional layer of human neurons, and simply by scratching the layer with a thin metal rod, they created an open ‘wound’ devoid of cells.

To ensure the gap would be exposed to a dense concentration of Anthrobots, they created “superbots” a cluster that naturally forms when the Anthrobots are confined to a small space. The superbots were made up primarily of circlers and wigglers, so they would not wander too far away from the open wound.

Although it might be expected that genetic modifications of Anthrobot cells would be needed to help the bots encourage neural growth, surprisingly the unmodified Anthrobots triggered substantial regrowth, creating a bridge of neurons as thick as the rest of the healthy cells on the plate. Neurons did not grow in the wound where Anthrobots were absent. At least in the simplified 2D world of the lab dish, the Anthrobot assemblies encouraged efficient healing of live neural tissue.

According to the researchers, further development of the bots could lead to other applications, including clearing plaque buildup in the arteries of atherosclerosis patients, repairing spinal cord or retinal nerve damage, recognizing bacteria or cancer cells, or delivering drugs to targeted tissues. The Anthrobots could in theory assist in healing tissues, while also laying down pro-regenerative drugs.

Taking advantage of the inherently flexible rules of cellular assembly helps the scientists construct the bots, but it can also help them understand how natural body plans assemble, how the genome and environment work together to create tissues, organs, and limbs, and how to restore them with regenerative treatments.

News Source: Eurekalert